Grappling with Controversial/Problematic Icons

We have all undeniably looked up to and enjoyed the work of certain artists, musicians, or writers spanning throughout history. Many have altered the chemistry of our brains or the course of our lives through their era-defining work. But to delve into their humanity, who these creators actually were/are in person outside of their public persona, will more often than not change our entire perspectives of them.

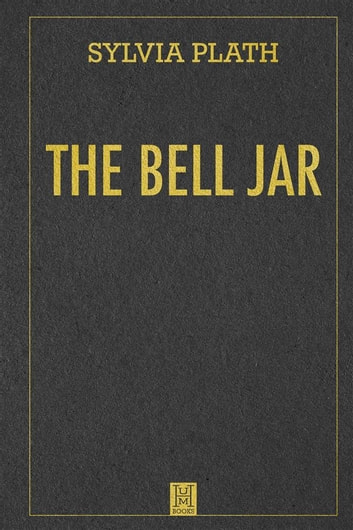

I recently finished the novel “The Bell Jar” by Sylvia Plath. Since then, I’ve been infatuated with her history and life. Born in Boston, Massachusetts in 1932, Sylvia Plath was one of the most iconic American poets and novelists of the 20th and 21st century. Plath began writing poetry as early as the age of eight, and suffered from severe depression, even undergoing psychiatric hospitalization throughout her life. With the publication of her works “Daddy” and “Lady Lazarus,” she began to gain national recognition for her poetic valor and expertise. In these two specific poems, she examined themes of parental abuse, male patriarchy, depression and mental illness, and gender inequalities. In 1963, “The Bell Jar” was published in London under the pseudonym Victoria Lucas. Strongly autobiographical, “The Bell Jar” follows a young college girl, Ester Greenwood, in 1950s America along her journey of aspiring success, mental breakdowns and psychiatric hospitalization, and eventual recovery. This powerful, influential literary piece also grappled with issues of patriarchy, feminism, identity, and mental illness, while criticizing a toxic American society. Personally, this novel spoke strongly to me and has empowered me to analyze and discuss such critical topics in my own life as well.

I have been obsessed with Sylvia Plath’s guttural, bone-chilling poems since middle school when my passion for poetry began. At that time I mainly focused on her poetic topics of female rage and empowerment. I did not understand her nuanced writing and overlooked the intensity of her poems in relation to abuse and mental illness simply because I could not grasp such pain. But with time, and especially after finishing “The Bell Jar,” I came to appreciate their dark intensity, yet truth and relatability. Unfortunately, however, with this passing of time, I also came to discover her problematic values and perspectives.

In many of her works, Plath is blatantly racist and anti-semetic. In “The Bell Jar”, Esther Greenwood describes her reflection as “a big, smudgy-eyed Chinese woman staring idiotically into my face” (Plath, 11). Later, when Esther Greenwood is hospitalized, she encounters a Black employee and server and describes him as incompetent, laughing/mocking, with huge rolling eyes, which are all stark racist stereotypes. In “Daddy,” Plath compares her abusive father to a Nazi. In “Lady Lazarus”, Plath equates her lifelong suffering and depression to the Holocaust, describing herself as, “A sort of walking miracle, my skin/ Bright as a Nazi lampshade,/ My right foot/ A paperweight,/ My face a featureless, fine/ Jew linen.”

Now, while her suffering is undeniable, comparing one’s pain to a historical genocide is outright disgusting. The horrors the Jewish nation had to endure during the Holocaust and in concentration camps is unimaginable. The only way possible to mourn for so many lost is through commemoration and remembrance. We must never forget, as to never allow such an atrocity, such a denial of and corrosion to humanity, to repeat itself. That is the only way, and to never disrespect those who have truly suffered through it. By equating one’s pain to a genocide normalizes such an atrocity and diffuses its seriousness. Consuming literary and cultural works containing such comparisons will make it permissible, or more so acceptable, for people to comfortably compare the Holocaust to their lives. I am not denying Sylvia Plath’s pain. But as a writer and artist, whose creations affected (and continue to affect) the world around her, whether she liked it or not, she must be held to a higher standard. The same goes for all writers and artists throughout history.

If I could speak to Sylvia Plath right now, I would express my pity for her. She’s iconic. Her writing changed the world. Her writing changed me. She has inspired me to write every day of my life, no matter what. But I’m genuinely sorry for her. I’m sorry for her suffering, the abuse she endured, and her mental and physical pain. But I’m even more sorry for the fact that she believed she could rightfully compare her pain to a genocide. I’m even more sorry for the fact that she was brought up at a time, by certain people, who confined her to a certain mindset and set of racist and anti-semitic beliefs. I still admire Sylvia Plath’s work and will most likely continue to read her poems and novels for the rest of my life. But knowing that a part of her identity is negative has largely ruined my respect for her.

And yet, I still don’t know her as a person. So can I really judge her? Can I really define her by these singular components of her life? Maybe she has an explanation. Maybe she doesn’t. We’ll never know. And that is the entire point. As readers, as viewers, as consumers, we will never truly know the artists. So what right do we have to judge them as people? We can only perceive and analyze what they choose to share with us. And when we discover an additional aspect of their lives, that very well may change how we feel about them. Does that not happen to us with other people in our lives? Exactly. It happens all the time. So, this is how I grapple with controversial icons: I appreciate the art they have gifted, and understand they have faults as humans, but ultimately I pity them for their poor judgments, hubris, and unfortunate life under the microscope of the world.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Hebrew Academy Of Nassau County High School. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.